In the Orondo-Chelan Area, Columbia River Valley, Washington

By Dave Tucker

In early 1984, some Wobs from the Bellingham IWW Branch began an apple orchard organizing project in the Chelan area. We all had at least a couple, and sometimes many, years experience in harvest and other orchard jobs. In February of 1984 we started up the IWW Orchard Workers Organizing Project (OWOP) in the Columbia River Valley of Eastern Washington for funding through the union’s membership and General Administration.

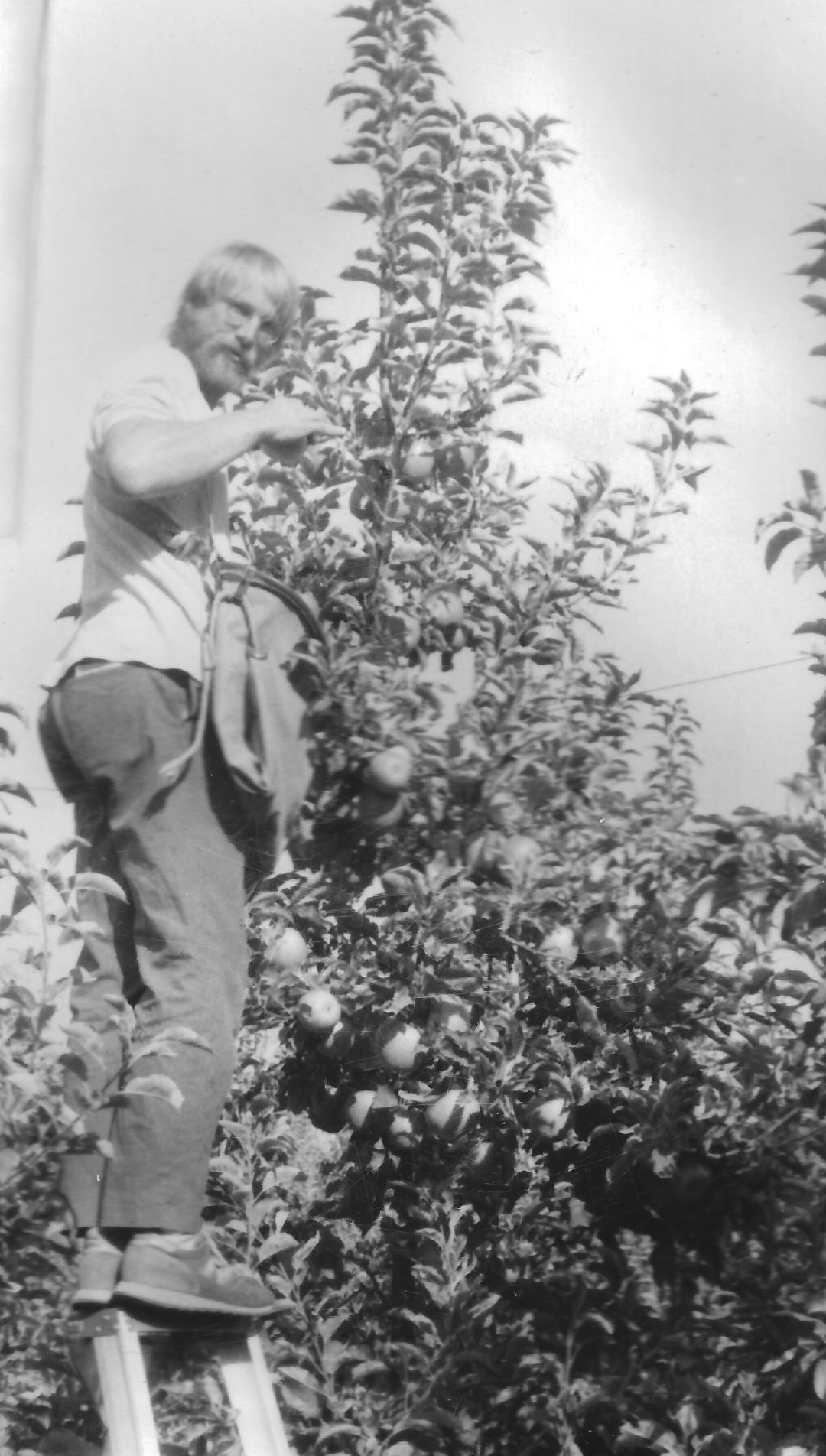

Apple harvest, from September into late October, draws lots of migrant workers. Today the workers are largely Hispanics and many of them are resident in the area, but back in the 1980s there were a lot of young white people from the cities. Fruit is picked from the ground and from ladders of various sizes. The picker carefully places the apples into canvas bags slung around your shoulders The bag, pretty heavy by the time it is full, is gently unloaded into 4x4x3 foot wooden bins — carefully because the fruit easily bruises; the boss can see the bruises and if the picker damages too much fruit, it’s down the road with you! It takes real skill, dexterity, and patience to pick fruit carefully but still fast enough to actually make some money. A bin holds around 800 pounds of apples. The larger the fruit, the fewer apples it takes to fill that bin, and the more money the picker makes. So pickers prefer orchards with “good fruit,” meaning larger apples — less work per bin. Back in the mid-1980s, a few growers paid premium prices ($10 or more per bin) to encourage slower more careful picking. A good picker could fill a bin in an hour, and 10-12 bins a day. Decent money in those days. But most growers paid $9, or even $8 on the corporate farms. Lower piece rates encouraged less careful picking, with a fair percentage of damaged fruit going to juice production. You get what you pay for. But a bin had to be full or slightly rounded, to get a bin ticket, which was the picker’s receipt for work done.

The main job issues in those days were piece rate, housing conditions, and usage of herbicide and pesticide sprays on or around workers. Those remain the issues today, 35 years later.

I sometimes picked on the Little Owl orchard owned by a relatively progressive guy, Damien, who specialized in production of boutique apples for the fresh fruit market. He had very high standards. It was easy to pick below his standards. He paid at least a dollar more per bin than any other growers, and provided decent housing for all.

In the 1980s his crews were entirely young white workers- Hispanic pickers had not yet begun to dominate the orchard labor pool north of Wenatchee at this time. When I picked in the early 1970s, there were a lot of “rubber tramps” in the orchards- older men who migrated with the harvest. By the 1980s, I saw very few of those guys.

I was the IWW General Secretary in 1983, so I missed the harvest. That season there was some discussion about forming an organizing committee. A Wobbly named Mike talked the idea up on the orchard where he worked but he only found a few workers interested in helping out; he told me that there was a general sentiment that improved wages and conditions were worth aiming for.

In 1984 we decided to get more serious. I was back from Chicago and needed work — that is, I needed money. We sought approval by the IWW Executive Board to use the old IU 110 ”harvest drive” assessment stamps as a fund raiser, to be sold by any IWW delegate who requested them. These dated from the late 1910s and were used to raise money to support the IWW’s Agricultural Workers Organization, and there were still a lot of them stashed away in drawers at GHQ.

We got approval for that in early 1984. I obtained a stock of the old stamps from the General Secretary. We marked them with “OWOP” and sent them off to IWW delegates and branches all over (even England and Australia!) to sell to members when they paid their union dues. They were $1 each.

We also requested cash donations from around the IWW. It was my job to provide regular financial statements.

We knew a few pickers in Bellingham who crossed over the mountains to work in the harvest. So Mike and I started getting people on board in the late summer, well before anyone headed off to the orchards. Over the summer we put up posters advertising organizing meetings, and the Industrial Worker published several stories about the harvest, encouraging footloose Wobs to come out and learn to pick, make some money, and help spread the word around the orchards Money started to come in from stamp sales, enough to fix up an old-style hand-crank mimeograph printing press that was sitting around the Tacoma IWW office and buy ink and paper for leaflets and more posters in the orchard country.

In 1984 harvest work began by mid-September. Mike was at Damien’s orchard with a couple others Wobs and friends. I wasn’t on the regular crew there, so I only worked there sporadically. It wasn’t hard to find picking work on other nearby orchards. One was a really big corporate operation, and I met a lot of pickers there. A couple wanted to make changes in conditions, but we never had enough workers ready to pull off job actions for a better piece rate. Little Owl wasn’t our primary organizing target, due to Damien’s better pay, better fruit, decent housing, and progressive attitude toward sprays and working conditions. So the first year was mainly spent getting a sense of organizing potential, making contacts on picking crews and with individual workers, and getting the idea of an orchard workers union spread around. The many obstacles for a union drive were the transient workforce, workers’ isolation on separated orchards, long workdays with little time to connect off the job, workers’ individualism, an absence of awareness of union ideas, and a lack of any central gathering point.

The mimeograph came into play to help break down these barriers. We produced the Pickin’ Times newsletter weekly in the fall of 1984. It was a two-sided rag that included stories of direct actions we heard about in the region to get better piece rates. The Times ran a survey on the ”pickability” of the newly-introduced Granny Smith apples that were becoming a popular high-profit crop. It also reported bin prices at various orchards, publicized union news and encouragement, and shared information about sprays and about state labor and industries insurance. We posted issues in various public places and stores around Chelan and in the general store in Orondo. I think a few made it as far south as Wenatchee. One tactic was to go out to various orchards at night and leave copies in partly-filled bins, or on ladders left in the orchard at the end of a day’s work. No one ever got caught (that I know of) sneaking around doing this. Three issues of the Pickin’ Times survive in the IWW Archive.

A few job actions around the region were reported to us, generally in the form of walk-offs and “march on the boss” tactics. These were described in the Pickin’ Times. One memorable IWW job action took place during the 1984 harvest. Several Wobs helped organize a quickie strike at McKay’s orchard north of Orondo. The grower cut his piece rate one day and the pickers (including me) rebelled. Since the pay was suddenly 10% less, we all agreed to put 10% fewer apples in a bin. When he came down on us for this, we simply said, “pay us full price or we’re gone.” We knew the fruit was very soon going to be over-ripe and much less valuable, and he’d have a hard time getting a new crew on short notice. Knowing that it would be fairly easy for one or two vengeful pickers to quickly and easily damage fruit already in the bins, he quickly agreed to pay the previous rate. We topped off the numerous partly-filled bins, and we got our bin tickets. The story was told in the October 1985 Industrial Worker as “Direct Action in the Orchards” by a picker named “Shortbin.” It is a real fun read and if you want a pdf, ask for a scan from belingham@iww.org.

The OWOP financial statement in the IWWs bulletin for February 1984 showed we had brought in a bit of a war chest: we had amassed the incredible sum of $591.

The 1985 campaign began with a call for footloose Wobs in the June ’85 IW. Three or four of us wrote postcards to the few workers who joined IWW in the 1984 season, as well as to our contacts we had worked with on various orchards. These workers were scattered all over the place, mostly in small towns with no other IWW presence. The members had essentially no contact with the union during the intervening months other than the IW and these postcards.

Harvest in 1985 got started, again among a few of us who returned plus at least one other Wobbly who came over from Tacoma to find work. That poor guy got a job in Chelan on an orchard with really bad fruit — small and few apples per tree. Took a long time to pick a bag. I remember he wrote a story and had learned a new Spanish word from a fellow picker: ‘¡malo! That guy screamed in frustration at how hard he had to work to make very little money and one day walked off in a huff. So did our Wob buddy. Also, Pickin’ Times wasn’t produced in 1985 because the ancient mimeo broke and we couldn’t get the replacement part.

1985 was our last year attempting to organize the industry. A number of members did not return to the orchards, including me. But we documented our effort in the February 1986 Industrial Worker, including some tactics we would have used in the 1986 harvest, such as translation into Spanish. We returned the OWOP fund to the IWW for use in other campaigns.